ODDITIES, RARITIES AND PENNY ARCADES

Rick Crandall

Would someone please find an Automatic Chime Bells machine for me? Or how about an Illustrated Song Machine or a musical bicycle?

Usually rare or non-existent machines surface immediately after someone sheds a bit of light on them. So if you want to see some wild music machines, read on.

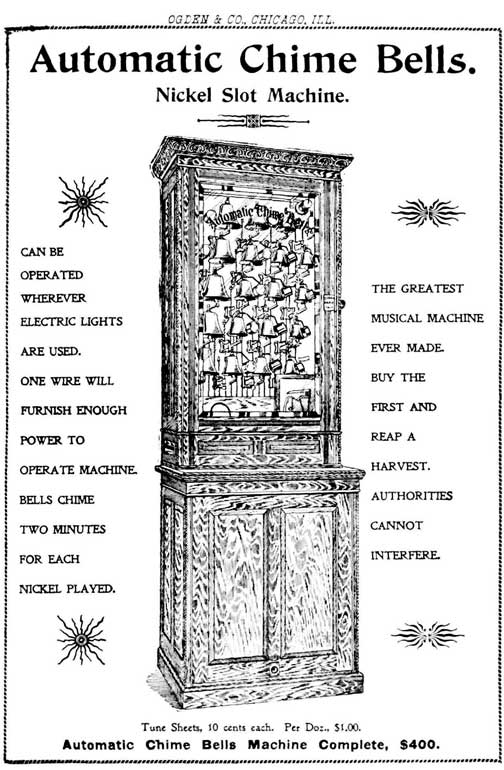

Automatic Chime Bells

I’m fascinated by the Automatic Chime Bells and its prominent position in an 1899 Ogden & Co. catalog. From the picture, we can imagine a nicely finished oak case with bevelled glass front and polishedbrass or nickel-plated bells—19 of them. The “tune sheets” were presumably paper rolls which played the bells, two minutes for a nickel.

It was too early for an Arcade machine, and with its coin slot it surely was not meant for home use. You would think after two continuous minutes of bell ringing, you would insert a second nickel just to get it to stop.

Competition for Automatic Chime Bells came only from the Encore Banjo and the Regina disc changers. Indeed, various Reginas were also carried in the Ogden catalog and at prices that were SI00 less than Chime Bells, even for the Regina 11″ changer.

There are no known examples of Automatic Chime Bells, nor do we know who made it. Ogden was not well-known as a manufacturer, but rather as an early prolific distributor of all kinds of gaming items including cards, poker chips, gambling machines, music machines, etcetera. Dick Bueschel, well-known coin machine author of Northbrook, Illinois, produced some information on Ogden. He found several ads in March through September, 1897, issues of Billboard magazine where Ogden was a self-proclaimed manufacturer of automatic slot machines with “. . .new designs every month. . .the largest factory in the U.S.” In 1897 (the year the Mills Novelty Co. was getting its start) that may not have been too boisterous a claim.

In any event, these Billboard discoveries could have led one to believe that Ogden may have manufactured Automatic Chime Bells itself. The Chicago firm’s 1899 catalog was surely one of the earliest illustrated guides to what was available at that time. The catalog was found as part of the Boyer Museum library (see MBSI Bulletin, Volume XXVII, No. 1, Spring/Summer 1981) and has since been reproduced.

Figure 1. Ogden & Co. Automatic Chime Bells.

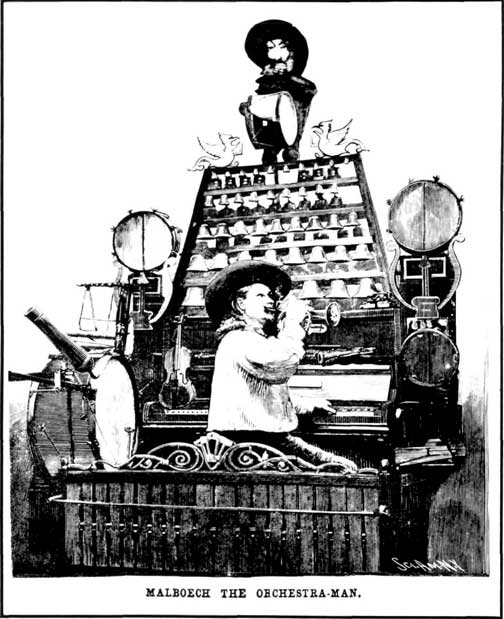

Figure 2. Orchestra Man.

Orchestra Man

One year later (1900) was a very eventful year for music machines. The Paris Exposition of 1900 had nine Encore Banjos on display, and in that year, Roth & Engelhardt began winning awards for its automatic pianos. The orchestrion hadn’t come of age yet, but instead we had Orchestra Man.

The February 23, 1(M)1, issue of Scientific American asserts that “There was much music to be heard at the Exposition of 1900, but the most original was, without any doubt, that played by M. Malboech. This extraordinary man is capable ot playing as many as thirteen instruments.”

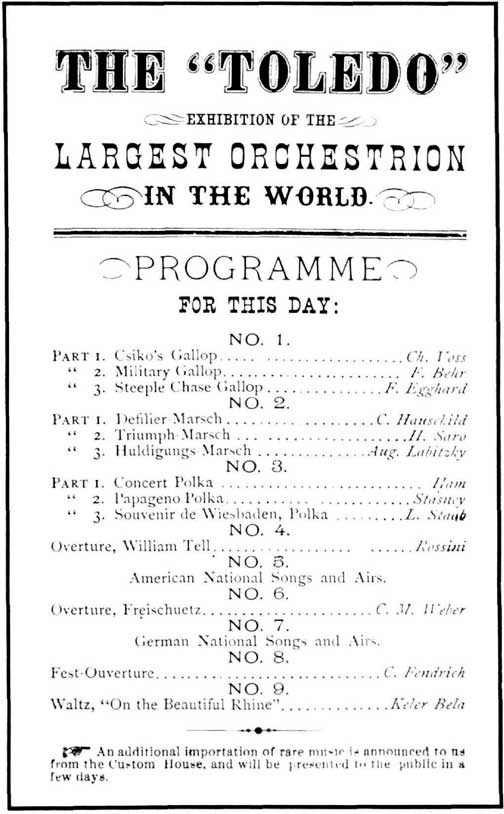

Figure 3A. Program for the “Toledo.”

Figure 3B. Orchestrion history.

The Toledo Orchestrion

While American automatic orchestrions were not a major factor until 1C>1(), the Germans were producing awesome behemoths 60 years earlrer based on large pinned cylinders typically powered by weights. A fascinating piece of literature described an incredibly large orchestrion in 1875. According to the article, its construction began at the close of the Franco-Prussian War in the Black Forest of Germany. This orchestrion could have been made by Welte. We know that as early as 1849 Michael Welte displayed an organ in Germany with 1,100 pipes. In 1865 he opened an office in New York City, New \ ork, and the first large Welte organ was sold to the Atlantic Garden in New ^ork. It too was called, “The World’s Largest Orchestrion.” Kaltenbach Brothers of Chicago, Illinois, brought the Toledo into the Inited States for the Centennial Exhibition at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1H76 in Brunswick’s Hall. The Toledo was immense at 32 feet high by 20 feet deep, and housed 1,632 pipes, 1,241 horns, drums and traps. It was claimed to be equal to an orchestra of 140 instruments. The case was made in the I nited States by Messrs. Kappes and Eggers of 103 South Canal Street. It surely must be fortunate that this machine is unknown today. The restoration cost would be infinite. And, think of the house addition some lucky collector would have to build to contain it.

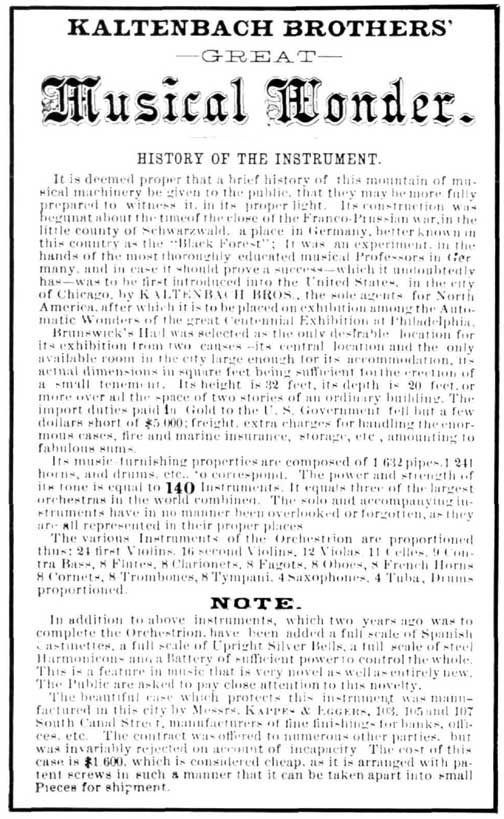

The Multiphone

No, this is not the automatic, cylinder, record changer of 1905, but a Rube Goldberg concoction of the Berliner’s Co. The April 1, 1899, issue of Scientific American pictures six phonographs strung together and operated by a common motor. This enabled accurate synchronization of the turntables so that all six could play the same record at the same time. Allegedly, the resulting volume was directly proportional to the number of records being played, although I would want an acoustics engineer to comment on whether that was actually true. The records had to be identical, but the article claimed: “Gramophone records are pressed from dies and matrices, like seals, under heat and pressure, and consequently all records of one catalog number are exactly alike in every detail.”

Record placement was critical, although somewhat downplayed by the claim: “The needle points are slid from the edge into the first record line—an operation requiring no special skill. “It has long been known that the carrying power of the ordinary gramophone is most astonishing. It fills half the size of the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. . .multiply the effect by six and you have the performance of a sextuplex gramophone.”

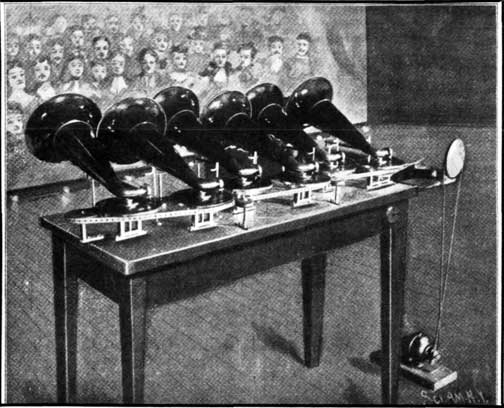

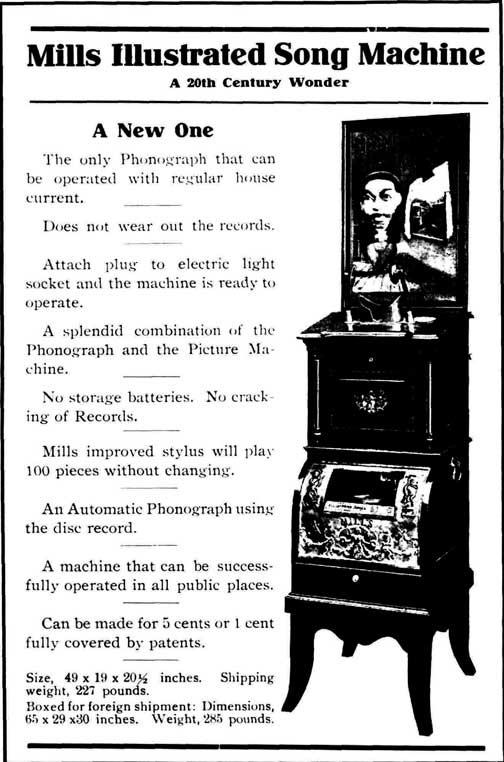

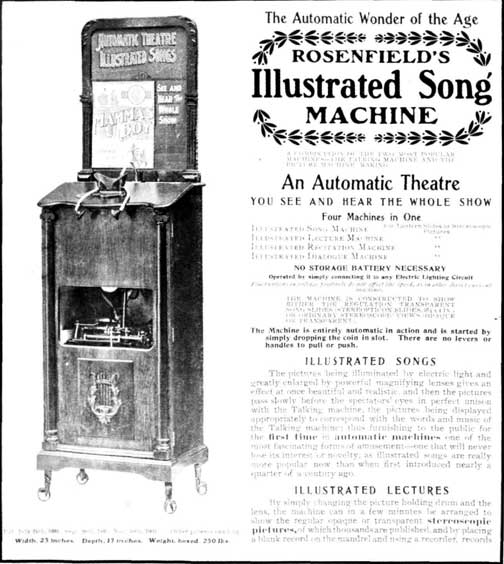

Illustrated Song Machines

The year 1900 marked the initiation of the Penny Arcade idea (according to the Mills Novelty Co., who should know). The Arcade became a focal point for early music-machine exposure. Here the standup ear tube phonograph came into popular commerical use, the most interesting versions being the so-called Illustrated Song Machine produced bv Mills, Rosenfield and Caille.

Figure 4. The Berliner Multiphone.

Where are these machines today? If you can believe the pictures and the hype, they were in extensive use from at least 1903 to 1915. An Illustrated Song Machine was a combination of a drop-card mutoscope and a cylinder or disc phonograph. Apparently the recording was unique to the “movie” and verbally or musically accompanied and complemented the picture series.

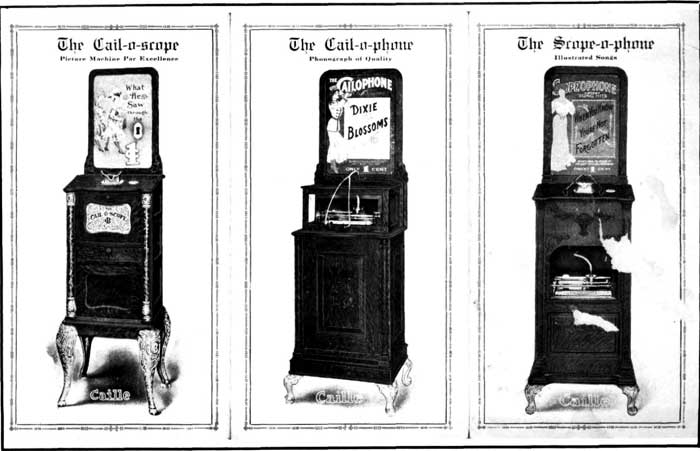

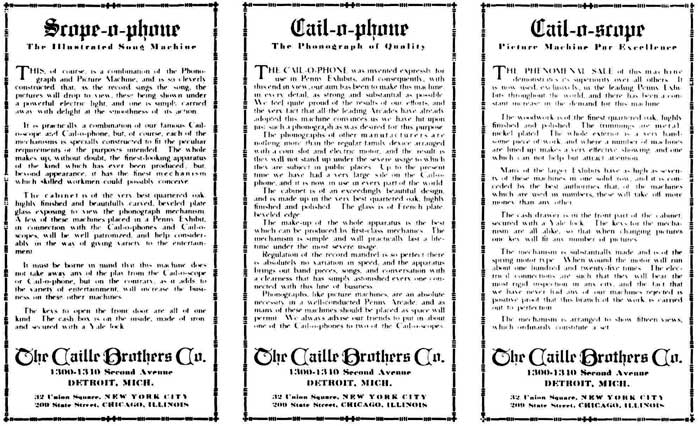

The Caille Brothers Co. of Detroit, Michigan, also jumped on the bandwagon and produced the Scope-o-phone, “The Illustrated Song Machine.” This was a combination of the Cail-o-phone phonograph and the Cail-o-scope drop-card picture machine.

In an undated advertising piece, Caille claimed: “. . .[The Scopeo- phone] makes up, without a doubt, the finest looking apparatus of the kind which has ever been produced. . .It must be borne in mind that this machine does not take away any of the play from the Cail-o-scope or Cail-o-phone, but on the contrary, as it adds to the variety of entertainment, will increase the business on these other machines.”

A 1907 Caille catalog shows the Cail-o-scope and Cail-o-phone and mentions 1907 as the first year the Cail-o-phone was on the market.

It would seem likely that the Scope-o-phone was introduced soon after in 1908 or 1909.

Figure 5A. 1906-7 Mills Novelty Co. catalog descriptions of the Illustrated Song Machine.

Figure 5 B. The Illustrated Song Machine with the disc phono viewable through the

lower window.

Figure 5C. Caille’s entries into Arcade music. These were cylinder players and

there is no indication that a disc player was made.

Figure 5D. An undated advertising piece.

Rosenfield may well have been the first with an Illustrated Song Machine. The 1^06 Rosenfield catalog featured it and even listed a number of locations using it. Interestingly, the Mills Novelty Co. and the American Mutoscope and Biograph Co. are listed as significant customers, yet they were soon to become competitors. Were they just spying?

The Rosenfield catalog claims: “. . . as illustrated songs are really more popular now then when first introduced nearly a quarter of a century atfo. . . ” Now, what was around in 18H2? They must have been thinking of something. Rosenfield was established in 1890 as a manufacturer ot coin-operated machines. Patents on some of its machines date back to July, 1894.

Perhaps the rarity of these machines is in some way connected to the way Penny Arcades operated.

Figure 6. Rosenfield’s Illustrated Song Machine.

Figure 7. Interior of the Song Machine.

Penny Arcades

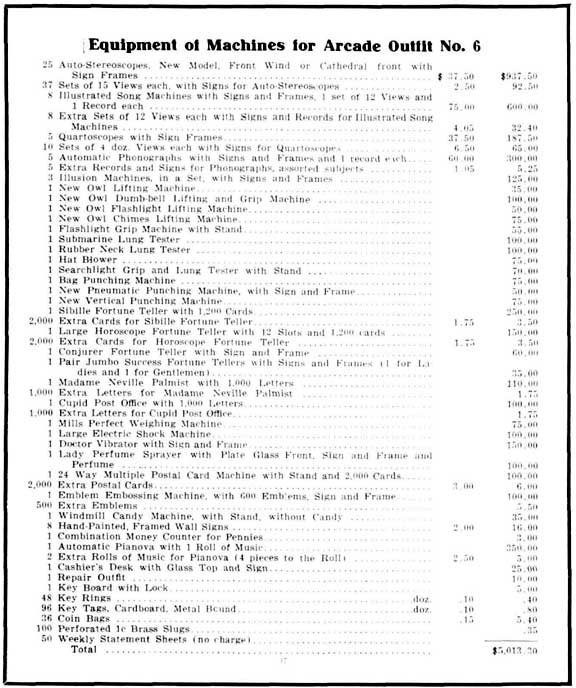

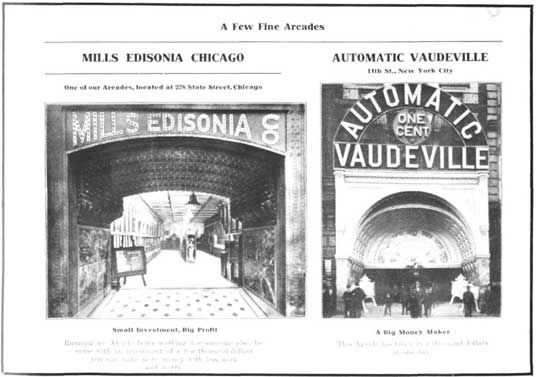

Mills actually produced a guide in 1907 on how to set up a Penny Arcade. Some excerpts are fascinating, and they provide useful information for collectors who desire to know more about the environment of the machines we collect. From the Mills guide:

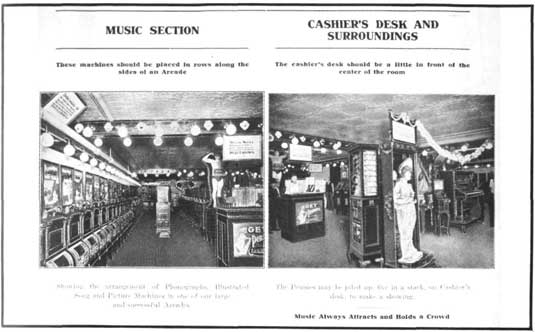

Generally speaking, there are two classes of places in which Penny Arcades may be operated. The usual one is the city location, a store room, located in the most populous portion of the citv. . . This kind of location is available for use the year round. Adjacent to nearly all cities nowadays, are amusement parks, which are constructed during the summer months only. A park is really an ideal Arcade location.

On the front of the building, by all means have a steady burning electric sign, reading “Penny Arcade,” “Penny Vaudeville” or some other suitable name, and add some suitable expression such as “Everything for a Penny.”

The walls of the Arcade should be neatly papered. A pleasing and durable decoration is obtained by covering the walls to a height of about five feet above the baseboard with burlap and above that with paper. The burlap is not easily torn or disfigured should it be hit by the machines, in moving them about, and a chair rail to separate the burlap from the paper not only provides a finish but prevents the machines placed along the walls from marring the decoration. The walls above the machines may be left plain or be panelled in an inexpensive way with molding placed on top of the paper.

In our experience it is best to place rows of machines along the walls, and if the room is wide enough, a double row, placed back to back, down the center of the room. Have the picture machines, phonographs and illustrated song machines in groups near the entrance. Place the larger machines along the walls and the small ones down the center.

It is very essential to have good music, as it always attracts and holds a crowd. Place the music in front near the door, so that it can be heard from the outside. It is necessary to preserve the best of order allowing no loafing, flirting or boisterous characters. Women and children are the best customers and an Arcade should be run in such a manner as to make it an appropriate place for them to visit. Pictures in all machines which show them, should be changed at frequent intervals at least every month, and the same applied as well to phonograph records. Keep close watch of the collection from each machine. When they appear to be decreasing materially, it is good evidence that a change is necessary. When any unusual public event, which attracts widespread nocice occurs, such as a great murder trial or a disaster like the San Francisco earthquake, the manager of an Arcade should be quick to avail himself of the opportunity thus afforded for reproducing through picture, phonograph and illustrated song machines, these events, as they will attract big crowds.

The Penny Arcade has disappeared as a phenomenon (although we certainly would call Chuck K. Cheese and Showbiz Pi/./.a restaurants electronic reincarnations) and perhaps the machines were junked on the spot. It is still hard to believe there are so few Illustrated Song Machines around after seeing them in so many Arcade pictures.

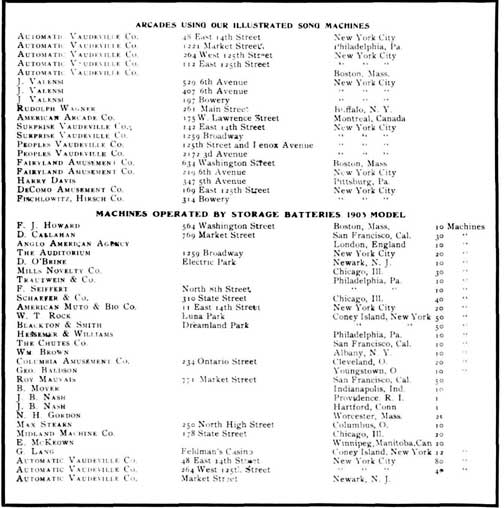

Figure 8. 1906 Rosenfield catalog listing of locations for the Illustrated Song Machine

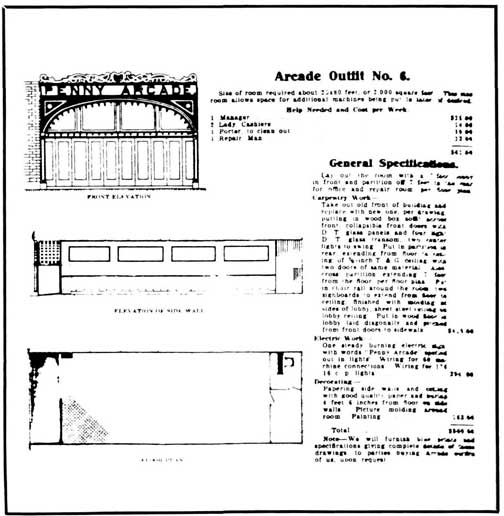

Figure 9A. Penny Arcade specifications.

Figure 9B. Note the prominent use of eight Song Machines. A Pianova coin-op

piano is included as well.

Figure 10. Look, there are 13 Illustrated Song Machines in a row from the Mills

1906-7 catalog.

Figure 11. The Mills Edisonia in Chicago (1906) appears to have more than a

dozen Illustrated Song Machines lined up on the left.

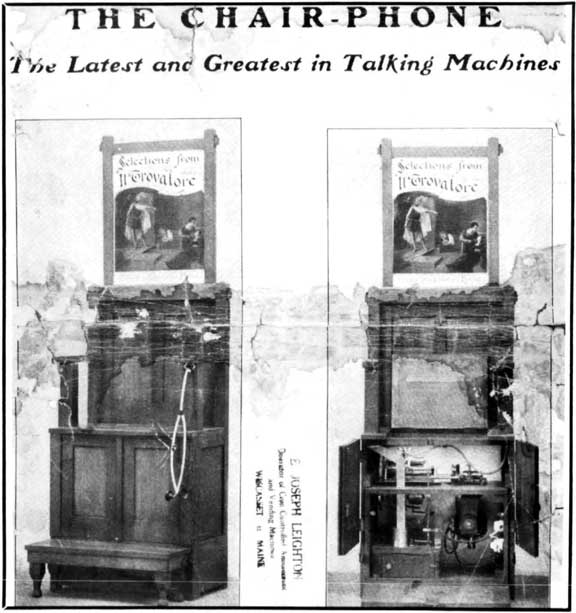

The Chair-Phone

Stand-up phonographs and Illustrated Song Machines were popular and follow-on ideas plentiful. Rosenfield’s idea of an innovation was the (lhair-Phone. The sales proposition for “The World Famous Rosenfield Talking Machine in The Form of a (lhair” was: Penny Arcades have compelled their patrons to stand up while using the machines, nevertheless they have made enormous profit. If Talking Machines earned so much under these conditions, their far greater earnings with Seats Provided is not surprising. How many theatres even with the best shows, could draw paying audiences if they were made to stand?

Figure 12. The Chair-Phone from Rosenfield Manufacturing Co., 585-589 Hudson St., New York City, New York, January, 1908.

Even the Grand Opera Houses with the greatest operatic stars, must provide seats to attract the necessary patronage.

Penny Arcades have not had the amount of ladies’ patronage they should have, but with the (‘hair-Phone, ladies are bound to be attracted.

Of course, we get a glimpse from the Mills book on Penny Arcades that the likely reason for Arcades not being popular with women was the presence of undesireable characters, which Mills advised operators to avoid.

The (-hair-Phone must have been introduced later in the life of the Arcade. The flier claims 5,000 Rosenfield machines in use whereas the 1907 Rosenfield catalog claims 2,000. This might help us date the Chair-Phone to the 1910 to 1915 period. None are known to exist today.

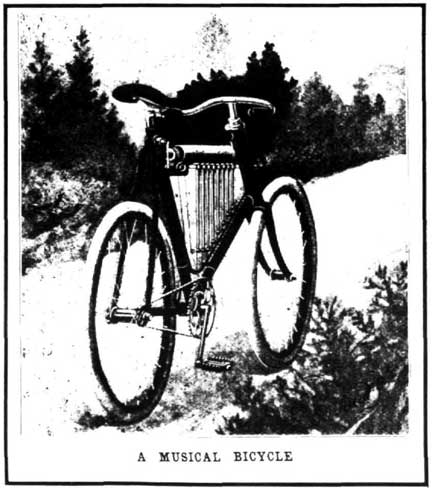

Musical Bicycle

Let us now leave the indoor world of the Arcade for the popular turn-of-the-century outdoor activity of bicycle riding. What does that have to do with music? Samuel Goss of Chicago, Illinois, (the land of mechanical music) had the answer. He invented a device to furnish music for the bicycle rider in 1898. It was a pinned-cylinder piano mounted in the frame of the bike between the rider’s legs!

Figure 1 3. A musical bicycle.

The cylinders were changeable and the inventor thoughtfully provided a way to turn the music off. Tempo control was provided by altering the speed of the bicycle. A March 26, 1898, Scientific American article billed it as “. . . an extraordinary companion for the bicyclist on his roamings, which are frequently lonely.”

This device could have also been the first version of automatic cruise control since “. . . the music only sounds well when the rider does not exceed a velocity of 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) per hour.”

Now here’s an amusing thought: “. . . in future a sort of orchestra band may be formed for the popular cycle parades by means of these instruments tuned to the time. As is well known, the music has been the most difficult part of these parades.” Do I detect tongue-in-cheek reporting from the venerable Scientific American?

Concluding Musings

The turn of the century was clearly a time of early formation of the automatic music field. As with any other new industry in its infancy, some new products hit the mark and established early leadership, while others just turned out to be hare-brained ideas pre-released to marker with exaggerated claims and entrepreneurial flair. Surely many, if not most, of the devices covered in this article are of the latter type.

But who knows what will now turn up. If something does surface, perhaps these disclosures will help identify it and draw it into the collectors world, thus saving it from possible discard and destruction.